Coby Dolloff and A. A. Kostas (try to) Tell an Adventure Story

the most ambitious collab of our generation

I’ve been talking for a while now about how Substack should attempt to move beyond the thinkpiece and into more robust forms of culture — poetry, storytelling, and the like. So I figured at some point, I’d better put my money where my mouth was (not that there’s much money — Coby’s Desk remains sans paywall).

But I couldn’t do it without a little help from my friends.

This post is a collaboration with A. A. Kostas, a brilliant writer who publishes poetry, essay, and fiction at Waymarkers, one of my favorite Substacks on the block.

We batted around a few ideas for collaborating — two-part essay, poetry slam, ongoing Notes beef, and the like. Finally, we wondered what it might look like to simply start off on a story, toss the narrative microphone back and forth hot-potato-style, and just kind of see what would happen?

And that’s what we did.

I’ll let you be the judge of the final product, but I can promise you that the process was a lot of fun. So without further gilding the lily, and no more ado, here is. . .

Coby Dolloff and A. A. Kostas (try to) Tell an Adventure Story

AAK:

Hey Coby, are you sure you want to do this? I know we joked about collaborating by telling a story together, but I’ve never seen two grown men write a story this way… aren’t things going to become somewhat —

CD:

— Unpredictable? Unhinged? Unreadable? Only time will tell, I guess.

In one sense, we’re not the first to do this. There’s a storied tradition of The Dialogue as a genre, but from what I understand, those were normally just one ancient Greek guy creating imaginary opponents he could dunk on. So this is a bit different.

The great Flannery O’Connor said that she only wrote because she couldn’t know what she thought until she read what she had written down. The great Michael Scott said something similar, I recall.

Really, we’re just carrying that idea to its logical extreme. The only thing more unpredictable than what I am going to write during any given appointment with the Muse is what someone else is going to write. So I suppose the two of us get to share a bit of a paradoxical joy: all of the magic of writing a story mixed with all of the excitement of reading one.

We can only hope the readers, too, share in the joy — and that they don’t judge that our baby would better be split Solomon-style.

And speaking of the readers, I’m sure I’m testing their patience already. What’s this thing supposed to be about, anyway?

AAK:

Hmm, I thought this was supposed to be a revival of the great oral tradition of two men speaking to a crowd gathered by a campfire, alternately entertaining their listeners with ribald jokes then disquieting them with strange and eerie suggestions, building the tension as the flames rise, uttering the denouement into the simmering coals, before finally drawing their audience’s eyes upwards to the cold, distant stars as their voices fade into the quickening dark. (I mean, a totally virtual, bloodless, disembodied version of that of course. Nobody wants to sit with real people by a real fire. Think of the smell, the bugs, the carcinogens. Ew.)

You mentioned in our last couple’s therapy session with Dr Frieda that you wanted us to go back to the good old days when we’d sip matcha lattes and tell stories together? You mentioned the tale of Praxis the Magnipotent, you said something about it being ‘the greatest adventure story never told’.

How did it start again? Something like: ‘In a morning in late summer, Praxis emerged from his home in the mountain village and peered out over the valley, and decided to seek — ’

CD:

Ah yes, Praxis — I remember that one.

In a morning late in summer, Praxis emerged from his home in the mountain village of Telos, peered out over the valley, and decided to seek his fortune. In many ways, the start of his journey was long in the making, even inevitable — the same as some now say about its conclusion. But more on that in due time.

Praxis was the village blacksmith, and for many years he hammered away in his forge — tucked away as it was in the highest part of the village, just against the Mountain pass. No one, said the legends, had ever gone out of the village and up the pass to the mountain above. No one had done so and survived, anyway.

Praxis was a lonesome, mysterious man. But an earnest one. Early in the mornings and long past sundown, we would hear the songs of anvil and hammer sing out.

I say we because I, too, lived in Telos then. Though it seemed a different place then than it does now.

I made my living as the town jester and sometime bard. This was, of course, before A-A-ron here came to town, and our twin troops of joke and song competed fiercely for the ear of the townspeople until we finally monopolized into the two-headed storytelling powerhouse you see before you today.

But I digress.

Praxis would hammer away in his forge like he knew he was making ready for something. Early in the mornings and long past sundown, we would hear the songs of anvil and hammer sing out. At times, we would pause a story or a song as the sound of the anvil would ring through the air like a church bell, calling all to attention. At times, I awoke panicked in the night, thinking some alarm was sounding or some act of violence being done — only to realize it was Praxis, hard at work in the forge as the townspeople slept.

Even then, it was as if he knew something. He worked like a man on borrowed time — or like one who knew his time would soon come. Many days I watched as he eyed the forge with his careful, arresting, inquisitive blue eye — as blue as the flame at the forge’s heart. I remember how caringly he would tend the flame, a silent statement that fire itself must be refined before it could play refiner.

But this was all before, well, before the Prophecy, if we can call it that — a part of the tale which, I suppose, you’re better equipped to tell than I. I still remember the look on your face when you first told me.

Night was waning to morning. Naturally, I was still haunting the Pint & Pickaxe. I’d had an ale or two and was subjecting the boys — and Rosie at the bar, of course — to my “Monarch’s River” story for probably the third time. It had just happened the week before.

You burst in the door, and I dropped my glass in excitement and sent it splashing all over the hardwood floor.

“Plenty of slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip,” I sighed, still smiling.

“Tell them what happened, Alex! Tell them the punchline!” I said, raising my empty glass in your general direction. “Tell them the punchline!”

But I had registered your presence before I registered your mood. By the look on your face I knew the story would not end the same way this time as it had before.

And you said, well — you tell them what you said!

AAK:

You seriously need to retire the ‘Monarch’s River’ story… three river sirens sent by cosmic forces to distract you from your quest to find treasure before a dam is opened to flood your friend’s house? It’s a little hard to believe, far too cinematic…

Anyway, I think you were up to the bit of your story where the river sirens were singing you a song of praise and about to turn you into a toad, when I burst through the door to tell you what had happened to Praxis.

He’d been up at the forge as usual, banging and clanging away, and curiosity finally got the better of me, so I climbed onto the roof of his neighbour’s house and peeked over the awning. Praxis had long, black hair which hung sweatily down his back and he had a whole lot of bunched up muscles on a rather small frame. But he dwarfed the figure I saw beside him, who was, it turns out, a dwarf.

This dwarf was saying something, muttering incantations as he passed Praxis a large, gleaming jewel, a ruby the colour of the setting sun. Praxis seemed surprised, but not shocked, and I watched as he placed the ruby into a hole in the handle of the massive, solid steel, two-handed shovel he was holding. Like the very object Praxis had worked day and night to hone had been waiting for the precious stone to be completed.

“Praxis of Telos, you shall bring balance to the universe with your mighty tool,” the dwarf said loudly, in a high-pitched squeak. “You will dig deep and in straight lines, to complete your quest and bring balance to the mystery of who you are and where you come from.”

“Thank you,” Praxis said soberly, bowing his large, sweaty head. “I pledge to complete my quest, and face any obstacle in my way, even death.”

The dwarf frowned and waved his little hands. “No need to be dramatic. You’re seeking truth, not confronting the armies of darkness.”

“Isn’t it the same thing?” Praxis said in his most gravelly voice, before swinging his shovel around and plunging it into the earth.

“I name thee Dialectic, the shovel of destiny!”

“Oh dear,” I heard the dwarf squeak to himself before scurrying away, back into the woods.

And that’s basically how I related it to you and the boys — and Rosie, of course — when I came to find you at the Pint & Pickaxe. I think I did a borderline offensive impression of both the dwarf and Praxis, but we can leave that to one side.

Anyway, this is where the story gets really interesting, and I think I’ll hand it back over to you, because you took your usual course of action and stuck your nose in where it didn’t belong…

CD:

Let me say that, first of all, I would normally be offended by that comment. I am quite sensitive about my nose.

But that night, it was my nose that was quite sensitive — because I did, as you say, stick it where it did not belong — literally.

So there we are at the P&P. I’ve got the people on a string. Rosie is laughing even harder at the Bible-hawking cyclops part of the story than she did the first time I told it.

Or at least that’s how I remember it, anyway.

But then you burst in and stole my audience — what with your dwarf impression and all. But, naturally, I am not one to let sleeping dogs lie. So I went out the door and told you guys that I was gonna have a puff on the ole Longbottom Leaf.

And that was half-true. But I think you knew what I was up to — you know me too well — because just after I stumbled out the door and toward Praxis’s place, you grabbed me by the shoulders and turned me 180 degrees. . . toward Praxis’s place. I had wondered why the uphill climb was feeling so much easier than usual.

Well, after a few detours, I got there by following my nose. There was a strange stench issuing from the forge. I checked the window and saw Praxis inside, poring over some kind of scroll by candlelight. So, stealthily, I snuck through the side gate and out back to the forge.

And by stealthily, I mean that the brick flooring beneath the gate out to the back yard had one of those changes in flooring level just subtle enough to escape notice — even the notice of the incredibly aware and erudite such as myself. I tripped over the bricks and, grabbing the gate to steady myself, sent it slamming closed with a “WHAP!” behind me as I narrowly regained my balance and found myself stumbling into the back yard.

There was a bright red glow emanating from the mouth of the forge. At first, I assumed it was just the fire, but on closer inspection, I saw that there was no flame at all. There was a massive shovel still in the forge, but the flame was out, and the shovel was cold to the touch.

But the red glow I had seen was emanating from the handle of the shovel — as was the sulfuric stench. It was the ruby you spoke of — glowing, hissing, pulsating flashes of red and puffs of smoke into the air around it.

I leaned in closer to get a look — and a whiff — of the thing, when suddenly I was knocked directly in the nose, backward by a burst of force and of light unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Knocked directly into a sturdy figure that had been behind me the whole time.

Praxis’s brawny hands lifted me to my feet, and I don’t know which sight I was more astonished by — him standing there beside me, or the shovel, midair in a cloud of blood-red smoke, levitating as if by some power of its own.

I looked at Praxis, and back at the shovel, and back at Praxis.

“I might’ve known, I’d find you here, little jester boy,” he snarled — though now, I remember there being just a hint of a twinkle in his eye, “Always sticking that misshapen nose in where it doesn’t belong.

“How’d you know to come here?” he badgered. His icy eyes were sharp and demanding.

“I promise, sir,” I stammered, “I just came to see if I could buy some hair jelly at Barber Wilson’s and stumbled in here by mistake,” — the town barber was next door — “I’ve had a few ales down at Rosie’s”

“Now the ales I can believe,” he quipped. “But buying hair jelly at the stroke of midnight? That’s a bridge too far for even someone as vain and ridiculous as yourself. I don’t think Barber Wilson has been awake past nine in twenty years.”

A light flicked on over the fence. “What’s that, young feller? Usin’ my name in vain, are ye? Guess I’ll have to step out back and investigate.”

By this time I had begun to gather my wits.

“The personal rancour in the first part of your remark I don’t mean to dignify with comment,” I said to Praxis. “But I’ll have you know that I have very good reasons for coming to Barber Wilson’s at this kind of an hour. He keeps his stock of hair jelly in that wooden shack over by the tire swing. I come up here at night and, err, borrow it when I need some. I think you understand – especially when Rosie’s at the bar! The old fart is none the wiser.”

“Here’s yer bill, whipper-snapper,” the old man said, holding out a piece of parchment as he walked — without stumbling — through the gate.

“I been bidin’ my time till I seen ya. Hopefully you ain’t spent too much down at the P&P! You reckon Rosie really likes them stories a’ yers? You think it ain’t got anything t’do with yer keepin’ that place in bidness 7 days a week and dubly on Sundies? Heeeheeheeeh.”

He began to cackle to himself. Red-faced from more than just the glow in the air, I snatched the bill from him and looked back up at Praxis.

“Don’t worry!” I stammered. “ I’ll never tell a soul what I’ve seen here, sir! I’ll just head out now and won’t tell a soul. . . after paying for my hair jelly, of course. The only reason I came up here was because my friends and the P&P had already gone to bed. Nobody else knows we’re here!”

Just then, I heard a familiar “WHAP!” and you stumbled into the huddle three of us had formed. We looked up at each other like two kids caught robbing the candy shop.

“Ah– Tweedle-dumb and Tweedle-dumber,” Praxis sighed, “I might’ve known.”

He shook his head.

“The gossipin’ town barber and two wannabee heralds. . . Don’t think I could conjure up three worse sets of eyes to see what’s taken place here tonight. Well, no, it’s not the eyes that’s the problem. The three of you couldn’t keep your collective traps shut if it was your divine duty. Only worse place for you than on the journey’d be stayin’ here blabberin’ about it. No sir, after seein’ what you’ve seen, I guess the three of you are comin’ with me.”

The two of us exchanged glances, followed by nervous shrugs. Praxis was not the kind of man you bargained with.

He rolled a scroll — evidently the one I had seen him reading inside — and stuffed it into his satchel. Sending us out in front with a little shove and firm application of his boot to our backs, he then proceeded to snatch the shovel out of its airborne perch. The red clouds dissipated.

“Now justchew wait a second,” Wilson protested. “I ain’t goin’ on no dahgum adventure. I’m too dern old fer this kinda tomfoolery — plus I got the shop to run!”

“Word has it,” Praxis smirked calmly, “that the representative from the barber’s guild is in town tomorrow — a week earlier than promised. I saw him check into the inn just this evening. I’m sure you been paying your dues to the guild, haven’t you, Wilson? Surely all the nights I’ve seen you playing cards down at Rosie’s has just been with the extra you’ve made in profits? Surely chasing drunks around at night with overdue bills is just part of your standard operating procedure?”

Wilson commiserated with the brick floor for a moment.

“Come ta think of ‘er,” he said, “a little time away might do me some good. Stretch the ole legs a touch.”

The twinkle returned to his wrinkle-bordered eye.

“And hell,” he said, “the three a’ y’all’d be plum stymied if I didn’t join ya. What you needs is a feller with the capacity fer abstract thought.”

That’s certainly not something you bring to the table,” I whispered to you.

“Curious,” Praxis muttered to himself, “Just like prophecy said. You will meet companions — though not the kind of companions you would seek.”

AAK:

Your memory is certainly amazing, I can’t remember half of those details and I’ve smoked way less Longbottom Leaf than you…

Anyway, yes it’s true that we reluctantly joined Praxis on his ill-fated quest, fulfilling a key element of the self-referential and vaguely-Calvinist prophecy, but for the sake of time and to cover for my rapidly failing ability to recall anything from more than a few days ago (who are you? what are we doing here? what’s a ‘stub sack’?), I’ll give a short overview of the boring middle section that makes up most quests.

We seemed to traverse many different environments and wear quite different clothing, all in rapid succession. I recall a road of yellow bricks and for some reason I was wearing a suit of metal and you were a scarecrow and Wilson the barber was dressed like a lion, and most bizarrely, Praxis was flouncing around in a dress that was giving ‘distressed Kansas farm girl’ while carrying his glowing red shovel that had taken on a distinct glitteriness.

I also remember us all as small, dwarf-like creatures but with bigger feet, no beards, and an obsession with breakfast foods; then we were running away from a chain gang to hide out in the bayou and find the buried treasure before a dam burst (but hadn’t we done this already?); then we were stuck in some sort of pixelated game, and I was an attractive red-headed woman, you were an overweight and effete scholar, Praxis was a bald and tattooed man-mountain, and Wilson became the most annoying person I’ve ever met; and then penultimately, before we reverted back to our more familiar selves, Praxis was a tall and stretchy alchemist, I was his incredibly attractive wife who could turn invisible, you were a rock creature, and Wilson was a flame who could fly…

Maybe, in hindsight, I shouldn’t have started growing and smoking that new strain of Longbottom Leaf…

Anyway, that all happened relatively quickly, and the shovel never stopped glowing red all that time, so when we arrived at what felt like our final destination, none of us were surprised that it was a graveyard.

CD:

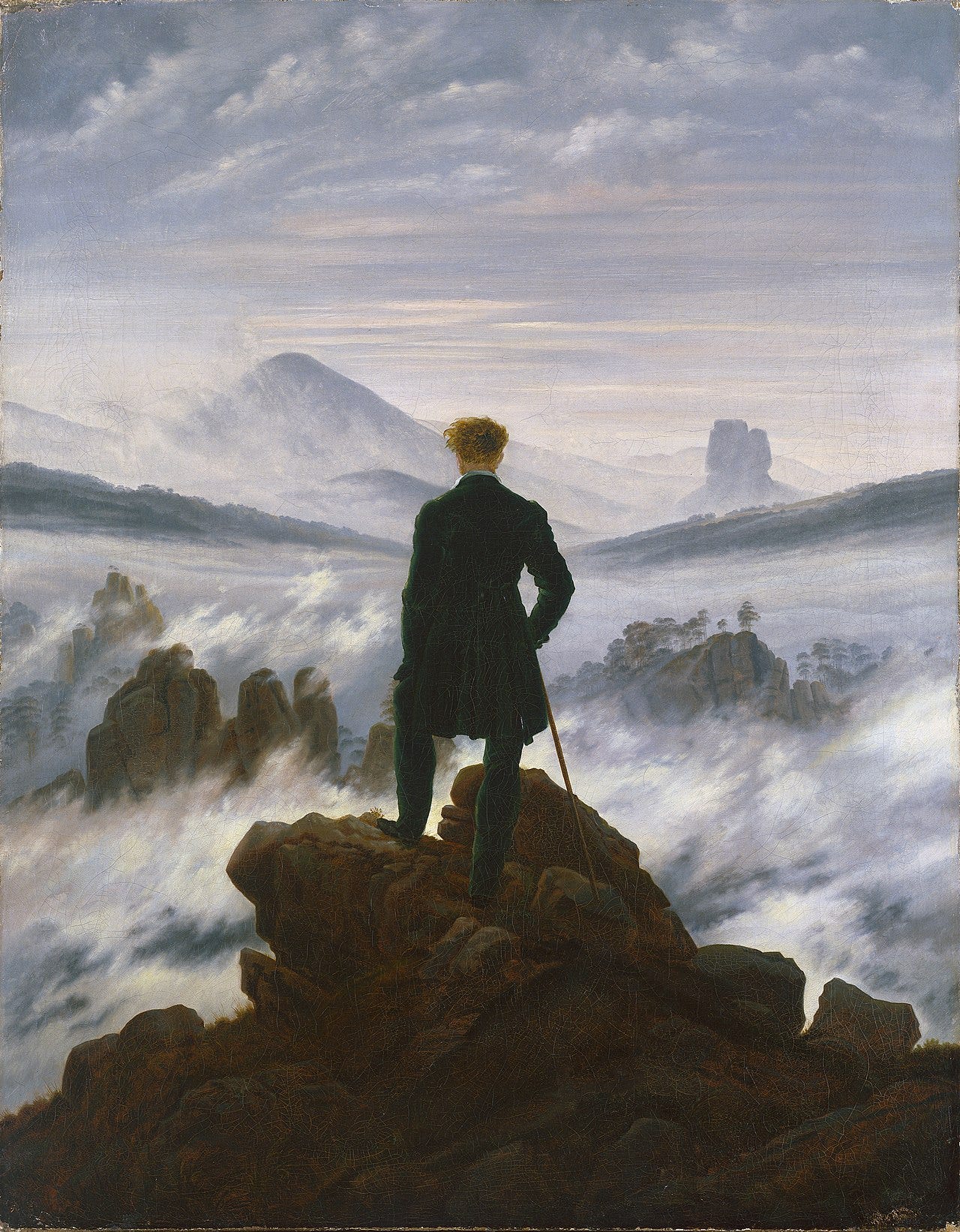

At the top of a mountain! A graveyard at the top of a mountain.

And far down the mountain below, at the pass, we could see our little village of Telos, small and distant and palpable, like a house in a snowglobe. We’d never seen it like this before!

It was as if we’d arrived where we’d begun — and knew the place for the first time. Someone should put that in a poem. . .

AAK:

Ahem, anyway, it was a graveyard.

Certain plots in the graveyard were glowing red, like the shovel was trying to find them. It was clear that Praxis should use his shovel Dialectic to dig deep and hopefully find the balance between his identity and his chosen village — to fulfill the prophecy and discover the harmony of Praxis and Telos.

“I never really felt like I belonged in Telos,” Praxis said with a heavy voice, and we all gathered around him for the kind of big hug which is inevitable once a group has become as close as we were. You don’t traverse through a montage of genres and identities without deep bonds forming, and even Wilson was starting to feel like part of the group despite his general old-man sleaziness and habit of running his fingers through our hair.

“Everyone in Telos is obsessed with endings and higher purposes and mountaintops. But I always felt stuck in the before, hammering away at my forge, more interested in the process than the result.”

We both sighed as if we understood, but I could tell from your furtive glances that you were as lost as I was.

I tried to respond helpfully. “Well maybe that’s what this shovel is going to help you figure out. Maybe you just need to… dig really deep?”

This seemed to cheer our friend up, and so Praxis squared his rounded shoulders and triangulated the distance between the shovel’s hexagonal blade and the rectangular plot glowing red before him, and swung the cylindrical handle in an arc into the dirt.

And then he dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug, and dug…

Well, you get it. It took a while. You, me, and Wilson laid down and watched Praxis toil away at his Promethean-Sisyphean-Herculean-Ulyssesean-Oedipal task. Wilson actually took the opportunity to give both of us a trim, as our hair had grown shaggy in our minutes-long travails through the many different environments. If I recall correctly, he gave you the ‘Trinitarian Godhead’ (three totally different hair styles on one skull, somehow distinct but harmonious) and gave me the ‘Quaker’ (an upside-down right-side-up bowl-cut made of hundreds of individual dreadlocks which shook whenever I moved).

Eventually, Praxis struck something other than dirt in the glowing red plots of earth. A wooden box, resembling a small coffin, which we helped him heave up out of the pit. You were terrified to open it, and I was petrified, and Wilson verified that we were both terrified and petrified. Praxis was mostly just irritated by us, so he pried the lid off with the tip of his shovel. You gasped, I rasped, Wilson clasped (his hands), but there was no corpse or skeleton staring back at us. Instead, it was a box with three shovels.

To our credit, it only took Praxis half an hour to cajole us into picking up the shovels and helping him with digging up the rest of the glowing rectangles. He ignored our soft jesterly hands, and our weak jesterly shoulders, and wouldn’t hear anything about your slipped disc from when you briefly worked as a professional somersaulter in the king’s court. And so we set off, spending the rest of the afternoon and evening digging away in the graveyard. And we set up camp that night and continued digging the next day, and the next. It seemed that no matter how many red glowing rectangles we dug up one day, there were just as many the next day. We had to build a more permanent encampment, with a proper shelter and kitchen and a well for water. And we sent Wilson back with a message for our friends in Telos, that we needed them to come join us, that we had found the answer to the problem of Telos, and that Praxis, that unassuming blacksmith, had become a kind of leader for us. His shovel Dialectic had found a way to synthesise the act of working towards something with the end-point of building it.

It all came down to digging a bunch of holes together with your buddies.

CD:

I’d say that pretty well sums it up! – as far as the actual events of the thing go, anyway.

Praxis just. . . kept digging.

As for the two of us, eventually our shovels stopped glowing red. After checking to make sure they weren’t just out of batteries or something, we took this as a sign that our work was finished. We informed Praxis of our imminent departure.

“It’s been a pleasure to goin’ alongside you boys.” He had that familiar twinkle in his eye again. “May your journey bring you swiftly to your destination — or may your destination be your journey. For in your beginning is your end.”

We both looked at him gravely as if we understood the weight of what he was saying — and then shrugged our shoulders at each other as we headed down the mountain, toward Telos.

“And don’t you tell NOBODY what you’ve seen here!” he shouted after us.

We followed that command pretty loosely. Or, considering his use of the double-negative, we followed it pretty strictly — it all depends how you look at it.

Of course no one in Telos believed us, either when we sent Wilson as a messenger or when we got back to town ourselves — and this was in SPITE of our unblemished reputation for unembellished truth-telling.

“Ha! Made it to the top of the mountain and survived! This is just another of your tall tales!” Rosie shook her head when we got back to the bar with our story.

“We thought. . . you was. . . a toad!” said one of our fellow regulars, opening up a shoebox on the table that held a pair of slimy amphibians. You rolled your eyes.

I sure had missed the ol’ Pint and Pickaxe — though since then, they’ve christened it the Pint and Shovel, in Praxis’s honor. They all pretty much assume the guy’s dead.

To be fair, no one has ever seen or heard from Praxis since. Sometimes at night I dream that I can still hear him digging, digging, digging — the same way he used to hammer away in the forge.

But funny thing, since that trip, I feel a bit different about our stories.

I care a bit less about the endings. A bit less about impressing everybody with them — even Rosie. A bit more about the telling. Maybe that’s why I get bogged down in the dialogue and the details — I kinda just enjoy the flavor of the thing. Maybe that’s part of what Praxis meant with all that journey and destination business. But maybe I’m just waxing sentimental, and maybe I’ve just had a shovel too many at the P&S.

You still hear legends around here that one day we’ll see Praxis again — that all that digging will actually lead to something.

The dwarf got into one of his prophetic stares again a while back and babbled something about the well we’d dug at the top of the mountain, and a great damn — or dam, maybe — that has been sealed at the heart of the mountain since the dawn of time, and a river finally reestablishing the eternal union between Praxis and Telos, running down the mountain with streams making glad the city, or something like that.

A bunch of spiritual mumbo-jumbo, if you ask me.

But come to think of it, I do wonder how he knew so much about the well we’d dug and what things were like at the top of the mountain and whatnot — maybe just from you and I blabbing about it.

He does seem to sometimes just know things. I asked him the other day if Rosie and me’d finally get together — and you know what the little rascal did?

He just pointed up at the P&S sign and smiled slyly at me for a few seconds. As if I was supposed to know what that meant.

I gave him a look that said “What in the Hades are you talking about?”

“The pint and the shovel,” he twinkled. “Buy her a drink. . . and just keep digging!. . . Sometimes you start a story and you have no idea where it’s going. You just hope you find it along the way . . .”

He looked up at me knowingly again, and winked, and nodded: “May your journey bring you swiftly to your destination — or may your destination be your journey. . . . In your end, is your beginning.”

And then as if for emphasis he put his hand under the bottom of my glass and sent it splashing across the floor.

He skipped, in his dwarfish way, to the doorway. I was in no state to give chase.

“Plenty of slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip!” he squeaked, and then skipped off.

“For us, there is only the trying. . . The rest is not our business. . .” I heard echo down the street in his wake.

“What a weird little dude,” was my first thought.

“Someone should really put that in a poem,” was my second.

And you know, Alex —

Today, we may not have told an adventure story —

With heroes, and humor, and courage, and glory.

But as the title above has implied,

Not a soul can accuse us of not having tried.